Paul Krugman writes an op-ed piece in the New York Times today, titled An Irish Mirror:

So what can we learn from the way Ireland had a U.S.-type financial crisis with very different institutions? Mainly, that we have to focus as much on the regulators as on the regulations. By all means, let’s limit both leverage and the use of securitization — which were part of what Canada did right. But such measures won’t matter unless they’re enforced by people who see it as their duty to say no to powerful bankers.

That’s why we need an independent agency protecting financial consumers — again, something Canada did right — rather than leaving the job to agencies that have other priorities. And beyond that, we need a sea change in attitudes, a recognition that letting bankers do what they want is a recipe for disaster. If that doesn’t happen, we will have failed to learn from recent history — and we’ll be doomed to repeat it.

I find his insistence on the need for securitization to be limited somewhat puzzling: the authors of his source material go out of their way to stress that securitization was not a major factor in the Irish debacle.

The source paper is a paper by Gregory Connor, Thomas Flavin and Brian O’Kelly titled The U.S. and Irish Credit Crises: Their Distinctive Differences and Common Features:

Although the US credit crisis precipitated it, the Irish credit crisis is an identifiably separate one, which might have occurred in the absence of the U.S. crash. The distinctive differences between them are notable. Almost all the apparent causal factors of the U.S. crisis are missing in the Irish case; and the same applies vice-versa. At a deeper level, we identify four common features of the two credit crises: capital bonanzas, irrational exuberance, regulatory imprudence, and moral hazard. The particular manifestations of these four “deep” common features are quite different in the two cases.

There is some support for the IMF’s thesis that stability of the funding base is important for overall stability:

In the case of Ireland, the capital bonanza was mediated by the Irish commercial banks. In 1999, Irish banks were funded primarily from domestic sources; see Table 1. By 2008, Irish customer deposits provided just 22% of domestic bank funding. Over 37% of the funding was obtained in the form of deposits and securities from the international capital markets. Directly in response to this capital inflow, the balance sheets of the Irish banks increased more than six-fold in the period 1999 to 2008. Lending to the non-financial private sector had grown to more than 200% of GDP by end of the period, approximately twice the European average (see Figure 5).

It is becoming more and more compelling to believe that the Basel Accords’ insistence that inter-bank loans should be risk-weighted according to the credit rating of their sovereign is a major contributor to financial instability.

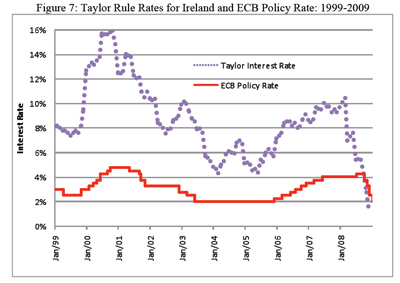

The authors also stress the relative looseness of monetary policy, as measured by the Taylor rule. This is food for Canadian thought, given the perpetual squawking over the Bank of Canada rate, which is by necessity applied nationally, over regions that can be performing very differently from each other.

After Ireland’s entry to the Euro zone, Irish banks funded much of their lending with short-term foreign borrowing. This allowed Irish financial institutions to extend much larger volumes of credit to borrowers at lower cost, as evidenced by Figure 6. As a small member of the Eurozone, Ireland does not have control of its interest rates, but Figure 7 shows an Irish target rate calculated from a standard Taylor rule. We set the target rate equal to 1/2 (GDP growth rate – 3%) + 1/2 (inflation rate – 2%) + 1%. Had Eurozone interest rates been set in accordance with a Taylor rule for Ireland, the interest rate would have been almost 6% higher on average during the period, and up to 12% higher in 2000.

As always, concentration is at the root of the problem:

Woods (2007) reports that, as a proportion of lending to the private sector, property related lending grew from 38% in 2001 to over 62% in 2007. With the enormous growth in property- and construction-related lending, the loan books of the Irish domestic banks were becoming increasingly undiversified.

Dr. Krugman glosses over a major similarity between the pre-crash climates in the US and Ireland. He believes that Fannie & Freddie’s role are overemphasized in the current debate; but they simply represent one way for the government to over-stimulate the housing sector. In Ireland the mechanism was different, but the results the same:

In addition to the enormous credit inflow, the over-heating of the property markets was exacerbated by government legislation that encouraged people to invest in property through a series of tax-incentive schemes. For example, generous tax relief was available to investors in hotels as the government sought to increase the stock of hotel rooms and hence tourism; similar breaks were available to individuals who built houses in seaside towns and in rural areas.

On the retail end, we can see some support for the Canadian regulatory response, when the maximum insurable amortization period was decreased along with the maximum LTV ratio:

A considerable decline in lending standards occurred in the Irish mortgage market; an increasing proportion of lending was done at higher loan-to-value, higher income multiples, longer maturities, and with interest-only periods. The only step the regulator took to stem the sharp decline in lending standards was to increase to 100% the risk-weighting on the portion of a residential mortgage written above an 80% loan-to-value threshold. As Honohan (2009) notes, this was a weak and ineffective response.

The familiar weaknesses of the American securitization process are dutifully trotted out, but the authors point out:

Despite its centrality to the US crisis, this particular moral hazard problem has no relevance to the Irish credit crisis. Throughout the bubble period Irish banks used the originate-and-hold lending system, for both residential mortgage and business lending. Almost all the loans that the Irish banks generated remained on their own balance sheets. This crucial component of the US crisis is virtually absent in the Irish case.

I have often criticized the lack of recourse in US mortgages; there is some skepticism as to the effectiveness of recourse in Ireland:

The property loans issued by Irish banks were obtained by wealthy property developers, arguably well-informed, rational actors with considerable business acumen. It is not clear whether a moral hazard argument can explain their behaviour. Personal guarantees were a standard component of property development loan contracts in Ireland during the bubble period, so most of these developers did not have recourse to the trader put option. Irish property developers are legally liable for the “tail risk” in the net value of these loans, including de jure claims against their personal assets.

This brings us to another potential source of moral hazard: weak law enforcement. This was likely an important source of moral hazard in the Irish case. The legal framework for personal bankruptcy in Ireland is antiquated and rarely activated. Although property developers signed de jure claims against their personal assets as part of their bank loan contracts, many commentators believe that these claims are de facto unenforceable in Ireland. There is also the concern in Ireland that politically powerful agents have the ability to manipulate regulatory and legislative processes to their advantages. Most large property developers in Ireland have been very closely connected to the ruling political party, Fianna Fáil. Kelly (2009) uses the term “too connected to fail” for this feature of the Irish business environment.

[…] Irish banks were last discussed on PrefBlog in the post Why weren’t Irish Banks Resilient? […]